JACK BRUCE: A MUSICIAN’S STORY- By Tony Paris

There's a lot to say about the high pressures of success, especially in rock and roll. The trappings are tremendous, sometimes tragic, always leaving their mark on the individual concerned. Yet it seems, especially in the cases of those superstars created in the Sixties, that if they flourish once more after their initial fame, we've deemed it necessary to give them a title, one to remind us of the pressures they've withstood. That crown of glory, of course, is the term "survivor."

But what about the ones that don't flourish again? They fall into their own categories. There are the fatalities. Jimi Hendrix never made it out of his brief reign, choosing instead, to martyr the cause, and in doing so remain eternal. Then there are the failures, the faceless many who disappeared, leaving no explanation as to their whereabouts. Deep within the framework, however, are those who no longer seek to surpass others' expectations of themselves, but choose to continue for the same reason that lured them in the beginning: music.

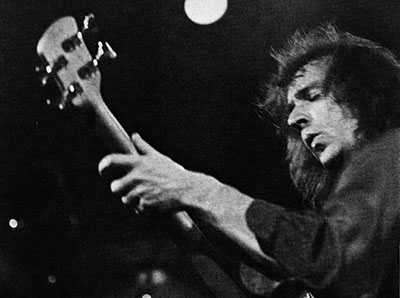

Such is the case with Jack Bruce. By the end of 1968, he, along with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker, collectively known as Cream, had pioneered a form of rock and roll which would prove to be the catalyst for rock bands for years to come. Hard-driving and energetic, their blues-rock styling was born out of each individual's working class background where music was an alternative to the factory or building site. By the time of Cream, however, each had proven himself a master musician, their merging thereby garnering the improvisational power trio the term "supergroup."

At the group's demise, Clapton and Baker continued together for one album in an over-hyped, aptly-titled band, Blind Faith. After that break-up, Baker quickly drummed himself into obscurity while Clapton chose a life of drug addiction and despair. Clapton always said he needed a catalyst for writing and drugs filled the bill. Once he triumphed over his pain, he was quickly on the road to recovery, Top-40 success and, subsequently, "survivor" status.

Bruce, meanwhile, chose to nurture the fruits of success in a subtler, some may say, more self-indulgent way. Rather than compromising himself in the superstar game, he surrounded himself with musicians more in tune with the sounds he perceived. His collaborations from 1969 to 1971, with players from his past (including Jon Hiseman and Dick Heckstaii-Smith) as well as some soon-to-be recognized luminaries (Chris Spedding and John Mclaughlin), resulted in three critically acclaimed yet commercially dismal offerings: Songs for a Tailor, Things We Like and Harmony Row. Songs For A Tailor and Harmony Row stand as two intensely beautiful LP's rich with the musical and lyrical interplay of Bruce and long-time collaborator Pete Brown (the two authored Cream's more popular and memorable tunes), while Things We Like is a more experimental instrumental set of incipient jazz-rock fusion.

After that trilogy, and a brief stint with Mountain's Leslie West and Corky Laing, Bruce spent the Seventies (musically) roaming from the avant-garde to the eclectic. He would lend his unmistakable vocals to Paul Haines and Carla Bley for Escalator over the Hill, then surface playing bass for Frank Zappa on Apostrophe. He released two more recorded projects, Out Of the Storm and How's Tricks, both in the vein of Harmony Row.

A classically-trained musician, the Scottish-born multi-instrumentalist jokes that his 17 aunties and 40 cousins all play the bagpipes, and that he never decided on music but rather it decided on him. Music, as with any form of art, is born within us; it's up to the individual as to whether or how to use it.

Most recently he has chosen to record and perform within the mainstream once again. A new album, I've Always Wanted To Do This, released earlier this year, includes Billy Cobham, David Sancious and Clem Clemson. And with the new record has come a tour- paced two days performing, one day off- to accommodate the fatigue Bruce finds on the road.

In a downtown Holiday Inn hotel room, Bruce is chain-smoking Camels. His eyes share the same characteristics found in much of his music- vibrant yet erratic. His manner is one of smiles and grins, set off by a dry sense of humor. He punctuates his words with laughter or occasional pauses to see if one understands the subtleties of his humor. The lines in his face, however, betray a more serious passage of time.

You've been playing music for more than 20 years. Why are you still doing it?

Well, I would've thought that rock and roll had got to a state by the Seventies where it could be more like the jazz scene was say, in the Forties or Fifties, where musicians didn't have to be typecast, they could move around. And, not being a rock superstar, just being a musician, I found it easy just to play with different people, as well as interesting and stimulating. That's why I still do it.

When you first met Pete Brown, wasn't he active in the Liverpool Scene and the New Departures [two factions of modern poets reciting poetry backed by a din of musicians]?

Yeah, I met him in Upperton's Road in 1962 (laughing as if expected to remember the exact date). January 17th. I don't remember. It was sometime in the crazy, early Sixties. He used to live in this house, this very famous house which was demolished. (It) was full of very strange people, musicians and poets and weirdos like that. That's when I first bumped into him. He let me live in his cupboard for a while. Only charged me six pounds a week.

Bruce a struggling musician and Brown the well-off poet?

Yeah, compared to me, he was well off. He was doing quite well ... had a cupboard.

You and Brown have been collaborators for quite a long time, and you've said he has gained remarkable insight into your mind. How does the writing combination between you and him work?

I usually have very definite ideas about the images and stuff, titles and things, but, of course, things change all of the time. He doesn't very often come up with a set of lyrics that I put to music ... I write ... a lot of the better lines, you'll find, are mine. He's not allowed to touch the music, but I'm allowed to touch the lyrics (laughter). I mean, he comes up with a lot of musical ideas, but I reject them all. I'm an egomaniac, like almost everybody.

Was Things We Like merely a self-indulgent effort?

No. Those were all things I had written when I was about 11 or 12 that I liked (and) wanted to record. I think a lot of composers- or people who write music - they get a lot of their ideas around about that age. They work on those same ideas all of their life. Those (songs) are like the basis for my writing that I wanted to record.

Usually I write in my head. I write with my head. I use the piano around to work on ideas. But if you're on the road, quite often you haven't got one. Most Holiday Inns don't provide them anymore. They used to. The standard is not what it was.

There's quite a difference being on the road now than in the Sixties, isn't there?

Well, things have gotten easier. It was much tougher then because there was no organization. Apart from the musical side of things, nothing was developed. There were no road managers - no real circuits to play. Those days were very hard because we were opening those things up. Now it's a lot easier because you have road crews and road managers. But the actual thing is still you get out and play and go from point A to point B, check into a hotel room, go to a gig, go back to the hotel room, go to the car, plane, room, gig, plane, and a plane and a room. And a bus.

We're at the end of quite an arduous tour. Obviously the glamour is beginning to wear a little bit thin by now. I'm tired. But that doesn't affect the gig. In fact it makes it better because everything else is so boring. You don't smash up hotel rooms anymore. Not very often, anyway.

Was it more fun touring with Cream or now?

Oh it's much more fun now. Cream was never any, well, in the beginning it was fun, but then it got too intense to be fun. It wasn't fun. I mean, as an individual I had a lot of fun in those days, but as a group we never really had a lot of fun together that much. Right at the beginning we did for a while ... two weeks.

They just worked us too hard, really. That's why, mostly why, that band didn't continue. In order for the band to be a success, the amount of roadwork that went into it was unbelievable. By the time we were a success we were all fed up with each other ... couldn't stand the idea of being that anymore.

After Cream broke up did you feel any pressure to come out with a solo album or had you been wanting to record one?

Yeah, that's what I wanted to do. I was asked to do a lot of things. I was asked to join Led Zeppelin. I was asked to join Emerson, Lake and Palmer. I was asked to join Stephen Stills. I was asked by Atlantic (Records) to form a new trio which would be the new Cream. I didn't want to do any of those things. I wanted to get deeper into my own music; deeper into the music that was coming into my head rather than the same thing or somebody else's thing.

Then the solo idea had been building in your mind?

Yeah. Also I could afford to do it then, having made some money. I could afford to do the things I actually wanted to do.

You've appeared on stage twice with Clapton and Baker since Cream's farewell performance in the fall of 1968. The first was at Baker's polo club - but it wasn't a concert...

We did a play called 'Cream in Your Jeans.' That's all . . . It was just an obscene version of life. No, it was just funny, a load of bullshit. I was Isaac Dogleash, Jewish Scotsman. I don't know why. Ginger. What was he? I forget now. Eric was something like Captain Madman or, no, the Mucous Kid. He was the Mucous Kid. Ginger was something like Drew Blood. I don't know… We got some real actors and we were the unreal actors and we just did it. It was fun.

As for the second reunion, didn't Cream play at Eric's wedding?

Yeah. That was nice too, yeah.

Quite a wedding reception.

Yeah. It was a small gathering. (Laughter) About five thousand people. Intimate. Some of the worst music I ever heard.

Nothing posh?

No. Absolutely not.

So much for laconic memories. Anyone who has followed Bruce's career knows it works in cycles - from touring and publicity to keeping a low profile for a couple of years. It doesn't bother him.

"I work between having children," he pauses, "I find that child-bearing is so tiring."

But once the post-natal depression is over, Bruce heads back out on the road under the only label he cares for, the one stamped in the space marked "occupation” on his passport: "Musician."